Boyz N The Hood (1991)

Dir. John Singleton

Written by: John Singleton

Starring: Cuba Gooding, Jr., Ice Cube, Laurence Fishburne, Morris Chestnut

Boyz N The Hood arrived in the summer of 1991, the debut feature from John Singleton who was fresh out of film school at USC. The film was both a box office and critical success, and Singleton would eventually be nominated for Best Director at the Academy Awards. He was the youngest person to ever be nominated for the award, and the first African-American filmmaker to ever be nominated for the award. The film likely stands as the high water mark for a career that has seen Singleton chart an interesting course, veering from his socially conscious early films to high profile gigs at the helm of Hollywood action blockbusters and franchise films. Through all of his creative divergences, Singleton has established a persistent thematic interest that ties his filmography together. Many of Singleton’s films serve as meditations on inner city violence and the systemic forces in America that contribute to the proliferation of violence and inequality in the African-American community, but never has he explored these issues as presciently or as urgently as in Boyz N The Hood.

Singleton began to develop the script that would become Boyz N The Hood while he was still a teen, basing much of the film on his own experience growing up in South Central L.A. The film begins with young Tre Styles (played first by Desi Arnaz Hines II, but later by Gooding, Jr.) being suspended from his school in Watts, and subsequently being shipped off to live with his father, Furious (Fishburne), in Crenshaw. As Tre grows, his father tries to give him advice and encourages him to avoid the temptations of crime and drugs that are so abundant in their neighborhood, and that could lead him down a path to destruction. Tre’s best friends, brothers Ricky (Chestnut) and Dough Boy (Ice Cube), choose radically divergent paths, with Ricky choosing football as an escape route from South Central, while Dough Boy graduates from petty crime as a child to more violent and reckless behavior as a teen, sinking deeper into the gangster lifestyle. Despite their differences, the three remain close friends and try to navigate coming of age amidst the turmoil of the constant violence that surrounds them. Ricky receives a scholarship offer from USC, and he and Tre sit for the SAT together, with the hopes that going to college will be their ticket out of Crenshaw. However, a chance encounter with a gang member pulls them both back into the violent realities of life for young African-American men growing up in South Central.

The film benefits from Singleton’s lived experience, as well as from the performances of its incredibly young cast. Besides Angela Bassett, who plays Tre’s mother, no one in the principal cast of the film was over the age of 30 when it was released, and many of the actors were barely in their 20s. Sometimes I think it takes a younger voice to really connect to the reality that inspires a film, and Boyz N The Hood is definitely the product of a young filmmaker willing to take chances and make bold statements. Singleton was protective of his script when it was being shopped to studios, insisting that he direct the film himself in spite of his lack of feature experience. He knew that someone from outside of the community represented in the film wouldn’t be able to connect to the story in a meaningful way, and the end result of his tenacity is a brave, emotional passion project. Boyz N The Hood explores the root causes of racial inequality in 1990s Los Angeles from a position of informed authenticity. The film doesn’t shy away from depicting graphic gun violence, but it never glamorizes violence, or hold it up as a spectacle, in the way that it often is in traditional Hollywood films. Instead, the film shows us violence as a cyclical phenomenon that has real and devastating consequences on the people and communities that it is acted out upon. Other films of the period that explore inner city crime and violence feel, at best, moralizing and stilted, and, at worst, exploitative. Boyz N The Hood feels like a dispatch from the real world, announcing the struggle of a real community that was heretofore largely underrepresented.

Growing up in the 1990s, I was aware that people of color had a vastly different experience of life in America than did White people like myself. From a young age I followed the news and current events, and I can remember seeing footage of Rodney King beaten on the side of the road by officers of the LAPD. I remember thinking that King’s skin color had something to do with the way that the officers felt they could savagely assault him. In my head, I tied these images to the ones I had seen in books of civil rights protestors being sprayed with hoses and attacked by police dogs, and I started to understand the concept of an institutional sort of racism that persists over generations and is less about individual acts of racial hatred, and more about an overarching denial of basic humanity and an attempt to maintain a repressive status quo. Of course, I didn’t come to all of these conclusions all at once, and certainly not at the young age of seven or eight years old, which I was when I started to consider some of these questions during the time of the Rodney King trial and subsequent riots, and the O.J. Simpson trial. It took time and life experience to understand the complicated issue of race in America, and watching Boyz N The Hood helped to put some of the final pieces into place. I’ve written before about using films as a way to explore other cultures or other experiences different than my own, and Boyz N The Hood was an early example of that in my life. I watched it for the first time when I was in high school, about the same age as the film’s protagonists, and while it didn’t open my eyes to a reality that I was blind to, it did present its central problems in ways that I had never considered them before.

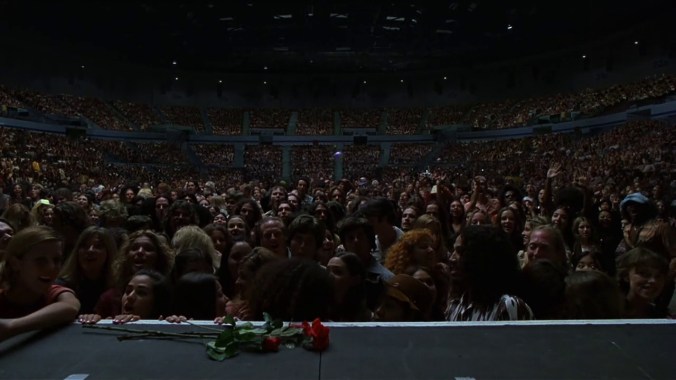

I’m referring to the scene in the middle of the film in which Furious takes Tre and Ricky to Compton and shows them a billboard advertising cash for homes. He introduces them to the concept of gentrification. This scene was also my first introduction to the concept of gentrification and to the economic ramifications of institutionalized racism. In under two minutes, Furious outlines the attempts to marginalize African-American communities through flooding them with drugs and guns, and by so doing to undermine and devalue African-American lives. He hits on the media’s ignorance of the societal problems of the African-American community, until those problems begin to cross over into suburbia or the “heartland,” at which point they are deemed “epidemics.” The violence of the film is a symptom of the larger disease of institutionalized racism, a centuries’ long campaign on the part of governments and corporations to delegitimize non-White communities. Keeping people fighting amongst themselves is a great strategy to maintain existing power structures, and agents of the State such as the police and the media exist to help foment that infighting, and to uphold the yoke of official power that is exacted over repressed communities. Hearing these sorts of ideas expressed explicitly in the film, coupled with a burgeoning interest in Socialism, helped to influence my worldview as a young man. Though I was a White man, I understood that I could stand in solidarity with minorities by trying to resist the influence of these power structures and exposing the fallacy of race as a factor of contention between people. The scene isn’t the most successful one in the film cinematically, as Furious’s sermonizing on the street corner to a magically arriving crowd of listeners simply feels a bit forced and inorganic, however, it is the most ideologically important moment in the film, because it helps to unpack the complicated gnarl of roots behind the pervasive violence shown in the film.

This scene likely sticks out as feeling somewhat inauthentic simply because the rest of the film is so naturalistic. As I’ve mentioned several times now, Boyz N The Hood is simply an authentic movie. The performances are nuanced, naturalistic, and emotionally resonant, and in many cases the performances belie the actors’ lack of professional experience. At the time known only as a rapper, Ice Cube steals the movie with his powerhouse portrayal of Dough Boy. He is both menacing and charming at the same time, displaying the charisma and onscreen presence that would lead him to a crossover career in films. In the early 1990s, Ice Cube was one of the unflinching faces of West Coast gangsta rap, but in Boyz N The Hood, he displays an emotional range not exhibited on his solo albums or with N.W.A. The scene where he and Tre carry Ricky’s lifeless body into his house after he is gunned down by a local gangster whom he had disrespected never fails to make me tear up. The loss of Ricky’s life is senseless, but something about the desperation in Dough Boy’s pleas that he be allowed to take Ricky’s infant son out of the room is the hardest part of the scene for me to watch. “He doesn’t need to see this,” he insists repeatedly, and there seems to be an underlying knowledge that this early trauma could lead the boy down a path towards the same vicious cycle of violence that Dough Boy himself is caught up in. That knowledge is certainly apparent in the single tear that Dough Boy sheds immediately before he pulls the trigger, exacting his revenge on Ricky’s killers. The bullet won’t bring Ricky back, and it will likely serve as a death sentence for Dough Boy, as well.

Cuba Gooding, Jr. also turns in an emotionally affective performance, portraying Tre as a young man attempting to claim his own masculinity in a world that is set up to undermine it at every step of the way. Though his friends are caught up in gang activity, Tre eschews violence and is generally a law-abiding young man. He takes his father’s lessons to heart, and even though he goes above and beyond to walk the straight and narrow, Tre sometimes still finds himself on the wrong side of forces of oppression. This is most obvious in the scene where Tre and Ricky are pulled over, profiled for “driving while Black,” and Tre is threatened by a racist African-American cop. During the traffic stop, both men are pulled out of the car, and Tre is forced up against the hood. “I hate little motherfuckers like you,” the cop says as he presses his gun into Tre’s chin, threatening to kill him. The police receive a call of a possible murder and let Tre and Ricky go, but the damage has already been done, as Tre realizes the truth in the cop’s words: “I could blow your head off and you couldn’t do shit.” This lack of power in the face of racist, State-sanctioned authority is at the heart of Tre’s crisis of masculinity. How can an individual reclaim agency in a system that is designed to deny him of his basic human dignity?

This is the question at the center of Boyz N The Hood, a film in which its characters are struggling to define personal success as something greater than simply surviving the day. Singleton begins the film with statistics about the homicide rate in the African-American community and ends it with a title imploring its audience to “increase the peace.” In between he paints a vivid picture of a generation rapidly being lost to drugs and violence, turning to nihilism in the face of oppressive powers often too vast to easily comprehend. He paints a picture of a community in crisis. I imagine Boyz N The Hood must have felt like a bomb dropping for audiences who saw it for the first time in 1991. I know that it felt that way for me when I first saw it some ten years later, and it still feels that way today over a quarter century after its release. Ricky’s death left me as emotionally raw watching the film a few days ago as it did the first time I saw it, and its questions of race, identity, and masculinity feel even more relevant today. The film drops knowledge but it also helps to foster empathy, and I think those are two of the highest purposes of any work of art.