Apocalypse Now/Apocalypse Now: Redux (1979/2001)

Dir. Francis Ford Coppola

Written by: John Milius, Francis Ford Coppola, Michael Herr (from the novel Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad)

Starring: Martin Sheen, Larry Fishburne, Frederic Forrest, Robert Duvall, Marlon Brando

This review is going to be a bit different, because I’m going to be writing a lot less about Apocalypse Now as a film, and a lot more about its presentation as a DVD, and about my experience with collecting DVDs in the early-to-mid 2000s in general. As I’ve mentioned before, those years when I was in high school and, to a lesser extent, early college, much of my disposable income was spent on building my DVD collection. The portability, special features, and relative low cost compared to VHS made collecting DVDs fun and easy. Though we know now that it isn’t true, it seemed, at the time, that this format would last forever, the discs not being subject to the same kinds of physical degradation that tapes could suffer from. DVD was sold as a format for serious film viewers and collectors, people who would be interested in listening to multiple full-length commentary tracks from directors and stars, people who wanted to see the footage that was left on the cutting room floor. DVD took the promise of Laser Disc and made it affordable and convenient for the masses. I bought in completely, and I often sought out “Special Edition” discs that contained hours of extra footage and bonuses about the movie. My copy of Apocalypse Now is just such a set.

The “Complete Dossier” collector’s edition of Apocalypse Now was released in November 2001, and was one of the first DVDs I added to my collection. It marked the first home video release of Coppola’s full cut of the film, entitled Apocalypse Now: Redux, which premiered at Cannes earlier that year. The set includes both the original cut of the film and Coppola’s director’s cut, which adds nearly an hour of extra footage to the film, spread out over two discs. It also contains a third disc with hours of special features, commentaries, and behind the scenes photographs and films. All of this is neatly packaged in a trifold case featuring stills from the film, and then inserted into a beige slip case, meant to mimic the look of the confidential file on Colonel Kurtz (Brando) that Captain Willard (Sheen) carries with him. The packaging is fantastic, and makes this collector’s set feel essential. The amount of material contained on the set’s three discs is overwhelming. Watching both cuts of the film would take up just under six hours, and the additional supplemental features could comprise an additional feature-length making of documentary if they weren’t broken up into bite-size pieces. Overall, it’s a great set.

Over the years, as streaming has become most people’s preferred method of media consumption, disc formats have become less and less extravagant. With the exception of boutique lines, such as the Criterion Collection, which are aimed at serious film nerds, physical copies of films are now often rushed to market with little fanfare, and precious fewer special features. Retailers are stocking fewer discs in store and the shelves are dominated by cheaply packaged new releases, aimed to make a quick buck off the folks who will come to pick up a physical release on day one, before they ultimately meet their end in a bargain bin. Gone are the days when a movie like Fight Club could become a cult classic based on its second life in DVD sales. In a post-Netflix, post-YouTube world, there is little need to own physical media. Behind the scenes footage is now the stuff of viral marketing campaigns, directors can provide commentary about the making of their films directly to the audience through a podcast or a Twitter feed. Though streaming may not have the fidelity of a BluRay disc, it can compare to any DVD, and is far more convenient. I can’t blame anyone for ditching physical media altogether, but, as is probably painfully obvious to this point, I still have a strong nostalgic attachment to these discs. The promise of insider’s knowledge that a good DVD set offered to me in 2001 is still something that I relish.

I can remember the first movie that I ever watched on DVD. It was the summer of 2001, and my family was visiting my grandparents in Upstate New York. At that time they had a cabin on a lake and for several years in a row, my family and my cousins, aunts, and uncles would vacation at the lake and stay at my grandparents’ cabin. During the day we would go out on the lake, swimming, fishing, or sit out and read, but at night time, there wasn’t much for us kids to do. We’d play cards or watch the Yankees game, but we never watched movies because the only tape I remember my grandparents owning was Doctor Zhivago. That changed in the summer of 2001. That summer, my cousin brought a PlayStation 2 with him to the cabin, and a stack of discs. I had heard about DVD as a new format of home video that would soon supplant VHS as the dominant video medium of the time, but the first time I’d ever experienced watching one was when he popped in Ghostbusters and I and my family gathered around to watch the movie, followed by nearly an hour of deleted scenes. I had seen the movie dozens of times by that point, but this viewing experience was like opening up a treasure trove of information about one of my favorite films. Immediately, I started scheming on ways to acquire a DVD player of my own.

Later that year, my sister and I made that goal a reality as we pooled our financial resources and bought a PlayStation 2, and I started to use the money I made at my first part time job building up a collection of movies, both new and classic. I remember fondly some of the first titles that I picked up: Monty Python & the Holy Grail, The Matrix, A.I., Fight Club, and, of course, my own copy of Ghostbusters. As I mentioned before, in its earliest stages as a home video format DVD was truly aimed at collectors and cinephiles, and these discs were all bursting at the seams with special features, commentary tracks, and deleted or extended scenes. Growing up, my family had taken frequent trips to the movie theater, and we often gathered in front of the television to watch movies that we’d taped during an HBO free preview weekend, but transitioning to DVD changed my viewing habits. I suddenly had my own movie collection, and movie nights became more of a solitary event than a family affair. I soaked up as many different stories as I could, and explored the commentary tracks and making-of documentaries included on the discs as I began my self-driven education in film.

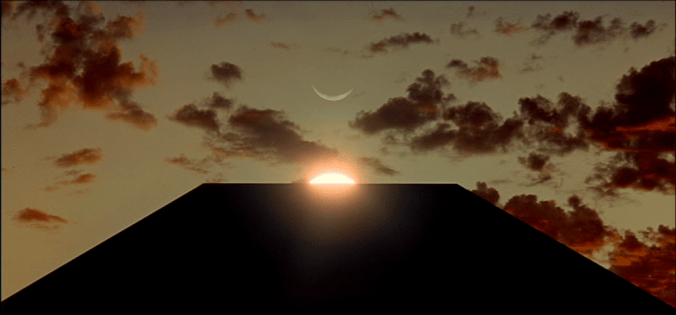

My copy of Coppola’s Viet Nam epic, Apocalypse Now, was an essential piece of that self-education. When I purchased the Apocalypse Now: Redux set sometime in early 2002, I had not yet seen the film. At that time, however, The Godfather was my favorite film, and I was eager to see more of Coppola’s work, particularly the universally revered Apocalypse Now. On initial viewings of the film, I had trouble breaking through the murky haze (both literal and figurative) that permeates the Viet Nam of the film, particularly in its extended version. Though it certainly doesn’t lack for action, Apocalypse Now shines a light on the horrors of war through revealing its characters’ reaction to increasingly dire straits. War is Hell, but in this film it is also madness, unjustly cruel and senseless. Apocalypse Now feels like a fever dream, the inscrutability of its imagery and narrative increasing as Willard traverses deeper into the jungle towards the mouth of madness personified in Kurtz. The film proceeds as a death march, following Willard and the crew of PBR Street Gang as they traverse up the Nung River into Cambodia. The river is frequently obscured by fog or smoke, a visual obfuscation that mirrors the lack of psychological clarity that these characters have in relation to their surroundings in a hellish warzone. Though Kurtz is singled out for assassination for having lost his mind and deserting, it’s clear that the war has robbed most, if not all, of these characters of some piece of their sanity.

When I first saw Apocalypse Now, I had never seen a war movie that was so thematically rich and dense with meaning and symbolism. At the time, I was watching movies like The Patriot, so to engage with a movie like Apocalypse Now that presented war so cerebrally was a major shift. For much of the movie, Coppola replaces the typical spectacle and bombast of the war genre with a more insular and meditative tone. Rather than propping up nationalistic or patriotic ideologies, Coppola’s film depicts the Viet Nam war with a healthy dose of skepticism for America’s interventionist military position. Willard’s mission to assassinate Kurtz operates as a microcosm of the war at large, cloaked as it is in secrecy, and undertaken with a dubious claim to the moral high ground. In Coppola’s vision of war, there are no clear winners or losers, only survivors, and even they seem to have been irreparably damaged by their experiences. Where a film like Saving Private Ryan (which I enjoy, and which is one of the great war films) presents the viewer with a tidy moralistic view of war, in which saving one man can somehow make up for the deaths of so many others, Apocalypse Now presents war as a scenario that brings out the basest, most animalistic instincts in men, and in which no one can expect to be redeemed. Apocalypse Now is a look into the savage, black heart of the individual and of society.

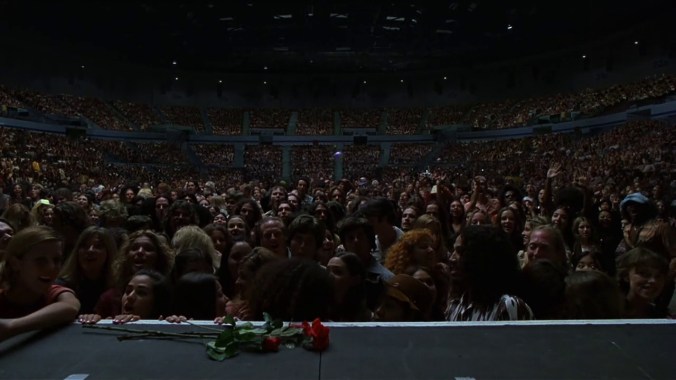

It’s always a pleasure to rewatch Apocalypse Now, which I believe to be the best movie about war ever made. The director’s cut of the film does add some interesting scenes that enhance both the strange, dreamlike quality of the film, and its anti-imperialist/anti-interventionist themes, but I typically default to watching the original cut, which is what I watched in advance of writing this post. One could teach a master class on film style with this movie. Form and content match as the film’s pace ebbs and flows like a river, the languid, dreamy scenes aboard PBR Street Gang intercut with flashes of brutal action, such as the arrow attack that kills Chief (Albert Hall). The lighting is perfect, particularly towards the film’s end, with Coppola often presenting Willard and Kurtz in total silhouette, or obscuring their faces with shadow, to reflect that darkness that they both share within. The acting is both naturalistic and inspired, from the leads down to supporting characters like Mr. Clean (a 15-year-old Fishburne) and Chef (Forrest), two members of the crew, and the unforgettable Colonel Kilgore (Duvall). The characters feel lived in and fleshed out regardless of how much screen time they get, with Brando’s performance as the mad Colonel Kurtz standing as one of his best, despite not appearing in the film until the final act. Apocalypse Now doesn’t attempt to make sense of all of the madness and horror, it simply allows it to be, challenging the viewer to respond to and reflect on it.

I think that I have such admiration for Apocalypse Now because of the particular way in which I was introduced to it. While it doesn’t exactly rank up among my favorite films of all time, it’s unquestionably a great movie, and, as I said, I believe it to be the best movie about war ever made. My understanding of the film was enriched by my ability to watch it in multiple cuts and replay specific scenes, or the whole film, over and over again. I was also given a wealth of supplemental material to put the film into a greater context and provide insights into the thought processes and working methods of the people involved in the making of the film. I have become so enamored with Apocalypse Now as a result of having owned it on DVD. I’m sure that I would have greatly enjoyed seeing it, but I don’t know that if I had seen the movie in a theater or just viewed it one time at that age, it would have made quite the impression upon me that it did. Being able to engage in a deep dive with the film provided me with a relationship to it that I rarely have to films that I see now, even ones that I greatly admire or objectively like more than Apocalypse Now. This project was born of a desire to explore physical media that I own, and while I mostly like to write about the movies themselves, it’s also important to consider the physical object itself sometimes. Apocalypse Now is a great movie, but I learned to appreciate it as a great DVD set, which in turn led me to discover its greatness even more.