The Elephant Man (1980)

Dir. David Lynch

Written by: Christopher De Vore, Eric Bergren, David Lynch (from the medical records of Dr. Frederick Treves)

Starring: Anthony Hopkins, John Hurt, Freddie Jones

As I mentioned when I was writing about Blue Velvet last year, I have been an obsessive fan of David Lynch’s work since I was about 16 years old. That film and Mulholland Dr. were my introductions to Lynch’s cinema, and they were the only films of his that I watched regularly until I came to college. The Elephant Man was actually one of the last Lynch films that I saw, never seeking it out until it was screened in a class that I took when I was a junior in college. At the time, the movie felt decidedly out of step with the rest of Lynch’s oeuvre, with its period setting and traditionally romantic narrative sticking out like a sore thumb among Lynch’s less direct, more decidedly surreal output. However, as I’ve spent more time with the movie, and as my own opinions on Lynch’s cinema have changed and evolved over the intervening decade since my introduction to The Elephant Man, I’ve discovered that it absolutely fits into Lynch’s strange filmography and shares a distinct affinity with much of his more overtly experimental and strange output.

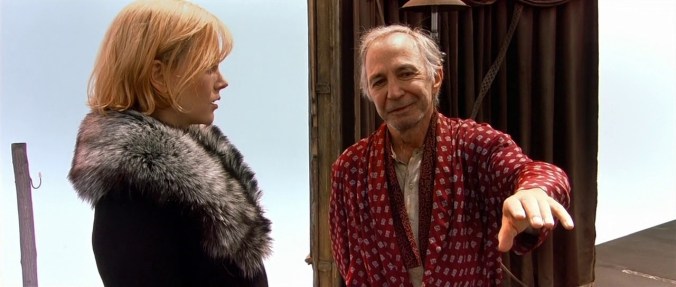

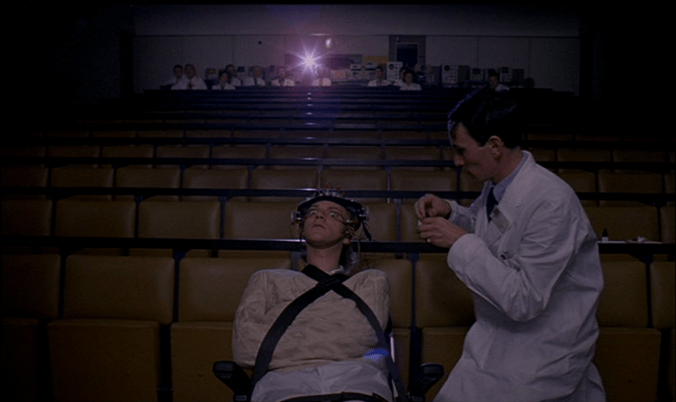

Based on the true story of Joseph Merrick (although in the film he’s called John), a medical anomaly who lived in England during the end of the 19th century, The Elephant Man focuses on the final portion of Merrick’s (Hurt) life during which he was under the care of Dr. Frederick Treves (Hopkins), and during which he gained a level of fame and notoriety in British society. The film opens with Treves attending a carnival freak show where a cruel and greedy master named Bytes (Jones) is displaying the unfortunate Merrick as an oddity that he has dubbed “The Elephant Man,” due to his unnaturally distorted and enlarged features and the preponderance of tumors that have given Merrick’s skin a hardened, scaly look. While the rest of the audience recoils in horror at the sight of Merrick, Treves recognizes him for what he is: an unfortunate human being afflicted with a debilitating and rare malady. Treves gets Bytes to agree to submit Merrick to medical testing, and Treves presents him to his colleagues at the hospital, where Merrick eventually is allowed to live as a ward. Though they initially assume that Merrick is an idiot, incapable of speech or advanced thought, the medical staff learns through Treves’s work with the patient that Merrick is, in fact, fairly intelligent and is quite capable of thought, emotion, and self-determination. Treves begins to work closely with Merrick, and as the two develop a bond, and the word of Merrick’s unique condition spreads, he becomes something of a celebrity, receiving letters from adoring fans and visits from members of the royal family. However, while he is enjoying the fame of celebrity by day, Merrick is still being subjected to brutal exploitation by night, as a porter (Michael Elphick) at the hospital has begun charging admission to sneak the curious into Merrick’s room where they can gawk at and mock the unfortunate man. Despite this daily torture, Merrick seems to take solace in his relationship to the kind Treves and maintains his quest for some small dignity up until the end.

Although The Elephant Man would seem to be an outlier in Lynch’s body of work, it actually has more similarities to his other films than might be initially apparent. Though this film and its follow up, Dune, a project fraught with tension and one that Lynch would ultimately disavow, find the filmmaker operating with the least amount of authorial control in his career, decidedly Lynch-ian motifs and themes abound in The Elephant Man. The most apparent aspect of the film that could be considered Lynch-ian is the character of John Merrick, himself. Throughout his career, Lynch has exhibited a fascination with the grotesque, the macabre, and the freakish, and the tale of poor, malformed Merrick is one that the filmmaker would seem to naturally gravitate towards. That he presents Merrick as a pitiable, complex character, rather than a monstrosity is also trademark Lynch, as he has shown a career-long sympathy towards characters in crisis such as Laura Palmer in Twin Peaks or Dorothy Valens in Blue Velvet. Lynch gravitates towards dark subject matter, but he attempts to find the light and the life in the characters that people his films, and Merrick is clearly no exception. Though the film, and by extension the filmmaker, certainly relishes the monstrous reveal of Merrick’s deformed body, a revelation that doesn’t fully come until 30 minutes into the movie, it goes out of its way to emphasize Merrick’s innate humanity and civility from that point on.

The film’s structure also belies Lynch’s influence. After Merrick arrives at the hospital, the day/night dichotomy that is so often present in Lynch’s work becomes the film’s operative framework. By day, Merrick is able to enjoy his time with Dr. Treves and visitors who look upon him with curiosity, sure, but of a more benign sort. Merrick’s daytime world is one in which he can aspire to some level of normality, and gain a modicum of acceptance within society. By night, however, Merrick’s life is a dark carnival led by the greedy porter, Jim, who is reminiscent of the drunkard Bytes in his exploitation and mistreatment of Merrick. All of the basic humanity that Merrick has been able to achieve through his work with Treves during the days is washed away as Jim turns him back into an inhuman monster, something to be feared and scorned, by night. When he isn’t being tortured by Jim and his band of morbid curiosity seekers, Merrick is tortured by nightmares, his restless sleep interrupted by visions of terrifyingly rampaging elephants. These dreams have a specifically surrealistic bent to them, and are reminiscent of Lynch’s early experimental shorts, particularly in their marriage of monstrous imagery to chaotic, industrial soundscapes. Though he was working from adapted material for the first time in his career, Lynch found ways in The Elephant Man to further his cinematic vision, and established patterns and artistic tendencies that would continue throughout his career.

This was the film that broke Lynch into the mainstream, as The Elephant Man was a major critical and commercial success. It’s interesting to see a filmmaker who would become known as something of an iconoclast working in a more traditional milieu, but as I mentioned, this isn’t some generic film without artistic merit and beauty. The black and white cinematography is at once sumptuous and primal, remarkably beautiful, but not in a gauzy or nostalgic way. Instead, the film’s imagery is suggestive of the dark, dingy world of turn-of-the-century London that Merrick inhabited. The film’s greys recall not just the skin of the elephants that Merrick was compared to, but the cold greyness of industrial machinery. This focus on the industrial is backed up by the film’s soundtrack, which often features a faint, impersonal thrum, as of a distant engine cranking away somewhere. Lynch uses the full array of cinematic tools at his disposal to create a rich and evocative period piece, including the famed actors who perform in the film.

Though Hurt was not yet a household name in America, which is part of the reason he was chosen to portray the deformed protagonist, Hopkins certainly was established as a renowned thespian by this point in his career. The two actors form a complementary pair, with Hopkins’s mannered, urbane performance giving the film a tranquil bedrock upon which Hurt can do his work. Though it would be easy to dismiss Hurt’s performance as being solely the work of the incredible makeup job that renders him totally unrecognizable, but it requires an actor of great sensitivity and poise to humanize the monstrous Merrick. Physically, Hurt renders Merrick’s anguished movements a grace that a man of his stature and predicament should not have, but the actor’s greatest work in the film is in his voice acting. Hurt uses a strained falsetto, giving Merrick’s voice a querulous timbre, both the result of his facial deformities and his constant mistreatment at the hands of others. Merrick stammers and stutters with the hesitance of a dog that knows it will be beaten for barking. Hurt’s belabored words drip with emotionality, revealing the broken, emotionally responsive and receptive heart that beats inside of Merrick’s chest, while his coal-black eyes reflect the deep despair that Merrick must feel. Merrick is a pitiable character by his very circumstances, but it is Hurt’s sensitive, emotive performance that brings him to life and helps the film reach heights of pathos and emotionality unseen again in Lynch’s filmography. In later Lynch films, displays of raw emotion are highly stylized, rendered nearly inhuman in their dissonance, but in The Elephant Man, Lynch gives in to sentimentality and Hurt’s genuinely plaintive performance shines through. It’s an exceptional and memorable turn.

Though it might feel like an early career diversion, The Elephant Man is actually an important film in the development of Lynch as an auteur, and one that marked a breakthrough into the mainstream for the director. Though his experience on his next film would likely prompt his turn away from prestige projects towards a personally-focused filmmaking, The Elephant Man proves that Lynch can helm a mainstream narrative film while also imbuing it with his unique cinematic vision. It isn’t a movie that I watch frequently; in fact I almost only bring it out when I’m going through a heavy Lynch phase in which I find myself watching through his entire corpus, but it’s a movie that deserves as much attention as his later masterpieces. The film is enjoyable enough on the merit of its beautiful cinematography and the captivating performances from its leads, but for fans of Lynch’s work, The Elephant Man holds hidden pleasures in its somewhat overshadowed affinities with the rest of his cinema. It’s a movie that I should probably watch more often, because I really enjoy picking out the instances of Lynch-ian weirdness that seep into the film at the cracks. It is probably the one Lynch film that I can unequivocally recommend to anyone, as well.