Big Trouble in Little China (1986)

Dir. John Carpenter

Written by: Gary Goldman, David Z. Weinstein, W.D. Richter

Starring: Kurt Russell, Kim Cattrall, Dennis Dun, James Hong, Victor Wong

Action films have been a popular genre throughout the history of cinema. Some of early cinema’s most widely-known and well-loved films could fall into the action genre in some form, whether they be crime films, Westerns, or chase films. As the genre developed, however, a certain type of pure action style started to develop. Westerns began to cede popularity in the 1970s to these more modern action films, and by the 1980s, the blueprint for the action film as we now know it was largely set in stone. Classic action franchises were born in this decade, including Rambo, The Terminator, and Predator, and those films would go on to influence the next generation of action filmmakers who would continue to evolve and grow the genre. A direct line can be traced from our modern action blockbusters to the over-the-top, bombastic thrill rides featuring Arnold and Stallone that were ubiquitous in the 1980s. During that decade, however, there was an alternative style of action film being developed, one that sought to blend genres in interesting ways, that borrowed from international influences, and one that depended more on its star’s charisma than his physique (although that wasn’t so bad, either). I’m referring to the action films created by the pairing of John Carpenter and Kurt Russell. These films, including Big Trouble in Little China, provide an interesting counterpoint to the more familiar action franchises of the time.

The duo teamed up for three movies in the 1980s and, though they weren’t all commercially successful on their initial release, Carpenter’s and Russell’s films have proved enduring. While their earlier films, Escape From New York and The Thing, were modest box office successes, Big Trouble in Little China had trouble connecting with audiences. Perhaps its blending of science fiction and action with traditional Chinese fantasy and folklore was too exotic for audiences in 1986. Maybe Kurt Russel’s performance, combining the lone hero of the action film with the wise-cracking leading man of the screwball comedy, was too unfamiliar. Whatever it may have been, Big Trouble in Little China had to wait to reach the level of appreciation that its director and star’s previous efforts had enjoyed. I saw all of these movies at different times in my childhood. They were staples on cable television on the weekends, edited for content and to run in the time allotted. When I was young, the gritty apocalyptic dystopia of Escape From New York was my favorite, but as an adult, I’ve become more and more fond of Big Trouble in Little China and all of its B-movie charm.

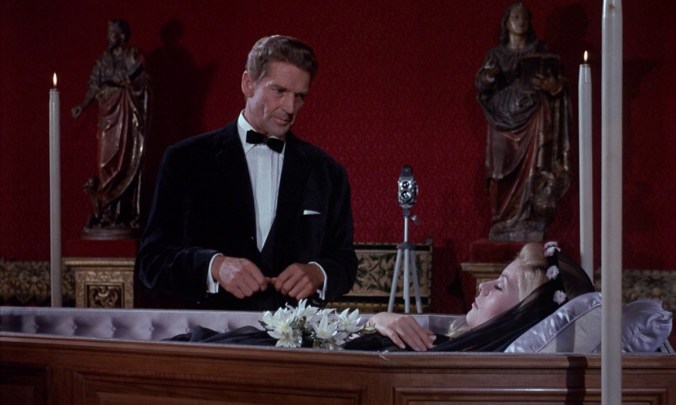

In the film, Russell plays Jack Burton, a fast-talking, fast-driving trucker, who finds himself embroiled in a gang war in San Francisco’s Chinatown. When his friend Wang’s (Dun) betrothed, Miao Yin (Suzee Pai) is kidnapped by one of the local street gangs, Jack agrees to help him rescue her. Along with the help of their friends Gracie Law (Cattrall) and Egg Shen (Wong), they set out to retrieve Miao Yin from the Lords of Death street gang. Their search takes them first to a brothel where they believe Miao Yin is being held, and Jack is successful in freeing many of the women being held there, but the rescue is interrupted by the Three Storms, three supernatural ninjas who take off with Miao Yin and take her to their master, David Lo Pan (Hong). Jack and Wang are again tasked with infiltrating a building to rescue Miao Yin, this time Lo Pan’s office front. When they get inside, they are again waylaid by the Storms and are introduced to Lo Pan’s sinister plan. Though he appears to be an old man, he is actually an incredibly powerful undead sorcerer, who is thousands of years old. He was robbed of his true physical body by the first emperor of China who placed a curse on him. In order to break the curse and regain his true form and his full power, Lo Pan must marry and then sacrifice a Chinese girl with green eyes, which Miao Yin has. From there, multiple rescue attempts must be made by everyone in the group as Jack, Wang, and Gracie all keep getting captured and escaping, all while trying to locate Miao Yin and prevent the wedding ceremony from taking place. The film’s final battle is a combination of traditional kung-fu, Wuxia, and slapstick comedy, as the heroes fight off the Storms and Lo Pan, rescuing Miao Yin. After everything settles down, Jack chooses to hitch up the Porkchop Express and return to the open road rather than staying in Chinatown with Gracie. However, just as Egg Shen says he will always have China in his heart, it seems that a piece of Chinatown is staying with Jack as the film’s final shot reveals that one of Lo Pan’s supernatural monsters has stowed away on his truck.

I didn’t know it at the time, but I likely have Big Trouble in Little China to thank for some of my later filmic obsessions. It was probably the first movie I saw that heavily featured Asian influences, despite having grown up in the ninja-obsessed early 1990s. I had seen shows like Power Rangers and even some Japanese anime when I was younger, but Big Trouble in Little China was probably the film that first introduced me to kung-fu and Wuxia, two genres that I would get into more seriously in my teenage years. I remember when I saw the movie for the first time, around the age of 11 or 12, thinking that it reminded me a lot of Indiana Jones, but more authentic and more exotic. The film was set in America, but it felt more immersed in Chinese culture. It seemed like a celebration of its influences, where the Indiana Jones trilogy felt more sensationalistic and exploitative. I probably didn’t give this a whole lot of thought at the time, but I now realize that the main reason the film feels so authentic is that it has an almost entirely Asian cast. Also, rather than relegating minorities to supporting and sidekick roles to a white hero, Carpenter places Wang and Egg Shen in the more traditionally heroic roles, while portraying Jack as, at best, a fish out of a water, but more often as a bit of a boob.

That’s another thing that I really appreciate about Big Trouble in Little China. While Jack Burton is definitely the main character of the film, he is far from the film’s hero. Carpenter deftly plays with Russell’s star persona, repeatedly placing Jack in positions where the other characters in the film have to come to his rescue. Russell plays Jack Burton as a swaggering man of action, modeling his performance on vintage John Wayne, but the film’s narrative often undercuts his heroism. Though he can more than handle his own in the film’s many fight scenes, Jack is frequently on the receiving end of punches that Wang is able to easily duck under or around. He’s inventive and unorthodox in his fighting style, but he’s also often a scene’s comic relief. This only works because of Kurt Russell’s natural charisma. He’s totally believable as an action star, but he also has a roguish sense of humor that is constantly on display in this film. Jack Burton is the ultimate cool guy, tough in a fight, but also able to be self-deprecating when the tilt doesn’t go his way. The wise-cracking tough guy was certainly a genre staple by this point, but mostly in the form of witty asides or scripted catchphrases. Jack Burton’s humor is inherent in his coolness, and it’s hard to see Schwarzenegger or Stallone being able to pull off the natural charm that Russell brings to the role.

Russell and the rest of the cast are aided by some great dialogue. The script went through several phases and rewrites, beginning life as a period Western, but as I mentioned earlier, the final product bears a strong resemblance to a screwball comedy with regards to its dialogue. Particularly in the interactions of Jack and Gracie, but throughout the film, the dialogue is snappy and articulate. The verbal sparring in the film is as entertaining as the fight scenes, with Russell and Cattrall displaying good on-screen chemistry. It’s one of the few action movies that is also genuinely funny throughout, without resorting to the aforementioned witty asides. Its humor isn’t nudging or winking, it’s subtly woven through the action, helping to establish these characters. Even a character like Egg Shen, whose role is almost strictly expository early in the film, gets some great lines. When discussing the hodgepodge of various mysticisms that influence Chinese spiritual belief, he says, “There’s Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoist alchemy and sorcery…We take what we want and leave the rest, just like your salad bar.” It’s a genuinely funny line, but it’s also a window into Egg Shen as a character. He’s obviously wise and worldly, but who knew that he had been to a Sizzler? It would have been easy for Egg Shen to have been a stereotype, as many other action films of the time probably would have portrayed him, but Victor Wong plays him with a mirthful sort of mysteriousness and the script gives him several opportunities to step out of his box.

I didn’t own a copy of Big Trouble in Little China until my late 20s. I grabbed it out of a bargain bin at a Best Buy one afternoon, and I’m really glad that I did. I hadn’t seen it in at least five years at that point, and I think I had forgotten just what a cool movie it really is. I think that all of the things that I really enjoy about Big Trouble in Little China are exactly the things that made it a flop upon its initial release. Mainstream American audiences just weren’t ready for an American movie that borrowed so heavily from Chinese culture. Obviously, Enter the Dragon had become a crossover hit in 1973, but martial arts pictures were still largely relegated to the grindhouse. Even the presence of emerging stars like Russell and Cattrall wasn’t enough to make the film bankable, as its deep dive into Chinese mysticism proved to be too confounding for its audiences. It wasn’t until home video really became a force in the late 1980s and 1990s that these types of films began to find an audience. Not surprisingly, Big Trouble in Little China found renewed interest in the home video market and has become one of the ultimate cult classics. It is the type of film that you can show a half-dozen different friends and each can come away enjoying something different about the film. Carpenter takes its series of disparate influences and mixes them up in a cauldron of 1980s action sensibility, churning out a wholly unique product that is more than the sum of its parts.