Dancer in the Dark (2000)

Dir: Lars von Trier

Written by: Lars von Trier

Starring: Björk, Catherine Deneuve, David Morse, Peter Stormare

It isn’t exaggeration to say that Dancer in the Dark is the most impactful film that I’ve ever seen. When I first introduced myself to the movie around 2002, at the age of 16, I hadn’t yet experienced a film that could be so heart breaking, so emotionally overwhelming. I had seen brutal horror films that inspired revulsion and fear, and a handful of films that were dripping with pathos like Roberto Benini’s Life is Beautiful, but nothing that had left me feeling as hollow and tired as that first time I saw Dancer in the Dark. The film is a portrait of human suffering, but it also examines the desire of the human spirit to persevere in the face of overwhelming odds and the desire of a mother to provide a better life for her son. Even though that first viewing was an emotionally devastating experience, the film very quickly became a favorite, and a film that I have returned to over and over again through the years. From Lars von Trier’s unique vision of a musical fairytale, to Bjork’s riveting, one-of-a-kind performance, I was fascinated by the film. Its soaring moments of fantasy and its sobering examinations of cruelty drilled their way into my brain, opening my mind to new possibilities of film style and of filmic representation. I’ve since seen films that more thoroughly or accurately examine emotion through cinematic art, but you never forget your first one, and Dancer in the Dark is a film that I owe a debt of gratitude to for changing my expectations of the cinema.

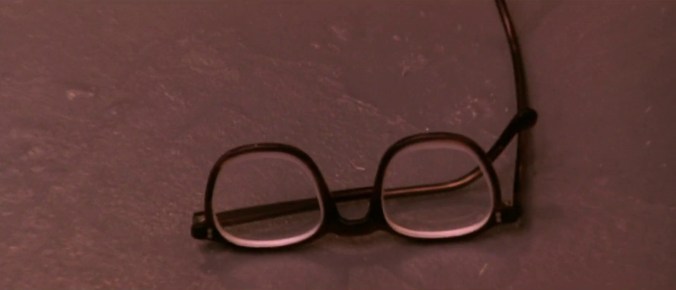

Dancer in the Dark is the final film in von Trier’s “Golden Heart” trilogy, and it operates as a fairy tale, similarly to Breaking the Waves. Another period piece, this time set in Washington State in the early 1960s, the film follows a similarly naïve protagonist, Selma (Björk), a single mother who emigrated from Czechoslovakia hoping to find better opportunities for herself and her young son, Gene (Vladica Kostic). Selma suffers from a hereditary vision condition, in which her eyesight has worsened to the point of near-blindness, and her only concern is saving up money so that her son can afford an operation that will reduce his chances of succumbing to the same dark fate. Selma’s devotion to her son is such that she is willing to work double shifts in a stamping plant and put together sets of bobby pins that she then sells for extra money, forgoing any creature comforts, simply on the hope that Gene will be able to enjoy a normal life with perfect vision when he grows up. Selma’s only pleasure in life is music and dancing, and she enjoys going to the movie theater to see classic musicals, which her friend, Kathy (Deneuve), must describe to her because her failing vision doesn’t allow her to see the screen. Selma wishes that her life were a musical, and is prone to childish flights of fantasy in which her friends and coworkers join her in elaborate musical numbers, bringing light into her dark existence. Selma’s pitiable fate is worsened when her neighbor and landlord, Bill (Morse), takes advantage of her disability and steals the money that she had been saving for Gene’s operation. Desperate, Selma is forced to go to extreme lengths to try to recover the money, and she pays the ultimate price for her devotion to her son and his future happiness.

Being bookends of a trilogy, it’s natural that Breaking the Waves and Dancer in the Dark should explore much of the same thematic ground. I’m not particularly interested in comparing the two films or discussing the merits of one versus the other, but watching them close in succession for this project, it’s difficult for me not to think of them together. When I wrote about Breaking the Waves, I wrote that it was a film that, although I admired it, I didn’t watch frequently because of its difficult and depressing subject matter. I have never had that problem with Dancer in the Dark. Though it could be considered a bleaker, more unforgiving, viewing experience than the earlier film, it’s one that I’ve returned to every couple of years, actually searching for the visceral emotionality that the film imparts upon me. I don’t know if it’s Björk’s performance as Selma, full of life and vivacity in the face of extreme hardship, that helps me to connect to this film in a way that I don’t with Breaking the Waves and Emily Watson’s more staid performance. Perhaps it is von Trier providing his take on a classical Hollywood musical through Selma’s fantasies that helps to break through the heaviness of the film, giving us glimpses of light throughout, while Breaking the Waves has the structure of a descent into Hell. Maybe it’s simply the fact that Breaking the Waves arrived on my radar much later in life, whereas Dancer in the Dark was a seminal film for me, and one that I discovered shortly after its initial release, allowing me to approach it in a much fresher context. Whatever the reason may be, I’ve clung to Dancer in the Dark for some 15 years, re-viewing it when I want to be broken down by art, when I want to feel deeply and painfully, when I want to be reminded that even though the world is a savage and cruel place, the love that we choose to hold inside of us is only extinguishable if we allow it to be so. It’s one of my favorite films ever made and a testament to the power of the cinema as an art form uniquely capable of depicting and inducing profound emotional and psychic experiences.

That being said, Dancer in the Dark is not a film for everyone. I have showed the film to friends over the years, and often I’ve been met with the same response: “Why would anyone want to watch something so unrelentingly depressing?” It’s a criticism that I can only partly understand, because I don’t really feel that Dancer in the Dark is a depressing film. It’s a heavy film. It’s packed with moments of genuine trauma, and it doesn’t shy away from depicting human suffering and cruelty of a heartbreaking magnitude, the whole time inviting the viewer to engage with it on a similarly heightened emotional level. It asks its viewers to cry and feel along with the characters, using techniques of suspense, pathos, and spectacle to produce immense waves of feeling, and I understand that that can be a difficult experience for some. Many people would rather see films that help to distract them from the pressures or troubles of their day-to-day lives, and I like to enjoy light entertainment, as well, but more frequently, I would like to engage with art that challenges me and helps me to explore facets of myself that I wouldn’t otherwise be able to engage. Art can and should be a means towards self-reflection and it should also help to build empathy. I have written often about using films as a window into life experiences and cultures that I don’t have firsthand knowledge of and I think that the same can be said for emotional experiences. While it might be difficult to watch a two hour film in which the protagonist is conned, robbed, commits a murder, and is, ultimately, executed, all while rapidly and tragically losing her eyesight, I find it to be a valuable experience as it helps me to learn about and engage with that suffering, ultimately becoming a more empathetic person. Watching the film is a traumatic experience, but I feel that having vicariously lived through Selma’s suffering, I come out of the experience as a better person.

Of course, empathy is only generated if the art is true and if the artists involved are pouring a great deal of themselves into the project. If this weren’t the case for Dancer in the Dark, it truly would be a depressing slog, akin to exploitative emotional pornography, however, largely due to Björk’s powerhouse performance as Selma, the film rings true and proves emotionally relatable. I can’t imagine anyone else but Björk in this role. I know that she is a divisive persona, and that her music and public image are often hard for people to digest, but I am an unabashed fan of her work and I wish that she would do more acting because her work in Dancer in the Dark, while unconventional, is devastatingly raw and true. von Trier takes advantage of Björk’s idiosyncratic voice and performative style in the film’s musical scenes, but he also draws an unforgettable dramatic performance out of her. As a nonprofessional and largely inexperienced actor, Björk’s performance is more defined by intuition than by technical acting chops, but that allows her to fully tap into the range of emotion that she has to portray as Selma. There is no critical distance between the actor and the role, and it’s clear that Björk is pouring every bit of her emotional self into the work. It’s obvious that she is fully invested in the performance, and, in fact, she found the experience of working on the film to be so traumatic that she has largely sworn off acting since. This is truly a shame, because the range that Björk shows in Dancer in the Dark hints at a natural aptitude for this type of performance, with her obviously shining in the film’s uplifting and uproarious song and dance numbers, but also nailing scenes of intensely personal emotional distress when von Trier chooses to strip away the film’s artifice and present us with a glimpse at a character truly in crisis. Björk is equally dynamic when portraying Selma’s quiet determination and her histrionic emotional responses, whether they be of fear, joy, or sadness.

The rest of the film’s cast is admirable as well. Their relationships to and with Björk’s Selma help to further audience identification and further heighten the sense of emotional empathy that the film strives for. Deneuve is a natural foil to Björk, providing a stability that is critical for both Selma and for the audience. Her Kathy is matronly, strong, and determined to protect her friend at any cost. In many ways, Kathy acts as an audience surrogate, informing the way that the viewer should react to Selma’s idiosyncrasies. She recognizes and celebrates the inherent goodness in Selma, looking beyond the unusual persona that she projects onto the world, and encouraging the audience to empathize with her, as well. Peter Stormare’s Jeff is another fount of empathy towards Selma, though his romantic desires for her largely go unrequited. Jeff is stoic and dedicated, showing up to pick Selma up from work at the factory each day, despite her repeated refusals of his offers for companionship. Though Selma is never cruel to him, it’s hard not to feel badly for Jeff, as Stormare’s typical hangdog performance style grants the character a great deal of pathos. Because he and Kathy so openly show a great deal of love and care for the unusual and sometimes inscrutable Selma, the audience’s bond with all of the characters is heightened. The film creates a web of emotional relations between these characters that feels real. It isn’t falsified, romanticized, or cheapened.

Dancer in the Dark is also the film that awakened my interest in the films of Lars von Trier. I wrote briefly about my relationship to the filmmaker when I was writing about Breaking the Waves, but I don’t feel that I really did justice to the way I feel about him as an artist. von Trier is frequently referred to as an “enfant terrible,” but I don’t think that this moniker really does his work, or his persona, justice. The director often makes headlines for his films’ perceived sadism and misogyny, or for his frequent controversial statements or gaffes in interviews, but I think that often these claims overshadow the true provocation that he provides through his art. I take the accusations of misogyny by his leading women very seriously, including by Björk shortly after filming Dancer in the Dark, however, more often than not, his actresses are the first to defend the filmmaker’s passion and vision, and even Björk has since walked back her stance. The superficial controversies in which von Trier often finds himself embroiled only serve to obscure the fact that though his art is challenging and controversial, he is one of the few filmmakers who seems interested in deeply and meaningfully exploring mental health, sexual power dynamics, and female identity through his films. Whether it is his place as a man to devote his work to these themes is a valid question, but I do think that his films are true, at least to the extent that I can personally relate to them. It’s important to remember that von Trier does not depict only female suffering, even in the “Golden Heart” trilogy. In Dancer in the Dark, Selma’s rich interior world, devoted friends, and boundless love for her son all serve as reminders that her existence is not just one of suffering. In fact, Selma’s death is even more heartbreaking because she is a fully formed character whose demise is snuffing out a vast world of potential beauty and love. von Trier’s treatment of his female characters may be somewhat problematic, but I do think that his representations are almost always respectful, and I truly believe that he feels with and for his protagonists, being far from the sadist he’s sometimes portrayed as.

I had a conversation recently with a coworker about movies in which the topic of favorite films came up. This is always an impossible question for me to answer. I have a stock answer, which we’ll eventually get to in this project, but really picking a favorite film, for me, would be like picking a favorite child. Instead, I gave him a list of a handful of films that I would be really interested in screening and giving a lecture on. I didn’t mention Dancer in the Dark, but it was in the back of my mind. Aside from Au Hasard Balthazar, it would be my obvious choice for a class or lecture on film and emotion. The films are radically different, although there is a bit of Bresson’s minimalist tradition in von Trier’s modified Dogme aesthetic. I’d likely have to give the nod to Balthazar if I were choosing, simply because of Bresson’s ability to muster the heights of human empathy in a film about an animal, but Dancer in the Dark remains the most emotionally moving film I’ve ever seen. Even after 15 years and more than a dozen screenings, it’s shockingly frank final scene never fails to leave me utterly devastated. I think that Björk’s performance as Selma should be remembered as one of the most unique and emotionally affective performances by an actor ever put to screen. It’s my favorite musical, and despite its imperfect fit alongside the other great films of the genre, it deserves a mention whenever classic musicals are brought up. It’s a film that I know not everyone will enjoy or appreciate, but I do think that it’s an indispensable film that anyone who wishes to educate themselves in the cinema must see at least once.